Giving Tuesday is a global day of giving back in and to our communities, it usually falls in the winter but given the surge of need, Giving Tuesday NOW has emerged. Here are a few ways that YOU can give back to your Central Texas communities NOW!

Pines and Prairies Land Trust Renewed its Accreditation by the Land Trust Alliance

Going Native at Billig Ranch

With only the smallest fraction of the native tallgrass prairie remaining in Texas, why go to all the trouble of trying to bring back the past? Much of Texas’ pastureland has been “improved” by planting imported, invasive grasses. While there may be benefits for domestic livestock, grasses such as Bermudagrass (and other imported exotics) work against our native wildlife and birds. They produce a low mat of dense, tangled grass structure. Most native grasses, by contrast, are bunch grasses. These clumps allow wildlife to develop intricate trails, critical to reproduction and foraging mobility. The taller overhead cover of native bunch grasses act as concealment from hawks and other predators while the tightly packed clumps of grass afford excellent nesting habitat. Lastly, many native grasses provide food, either directly in the form of seeds or indirectly as hosts for insects. Some of those insects are pollinators. The enormity of difficulties facing prairie conservationists can be overwhelming. Everyone knows converting to native grasses is not easy ... but where do you start?

Constituent Survey

Second Saturday Service Day at Yegua Knobbs Preserve

by Courtney Young

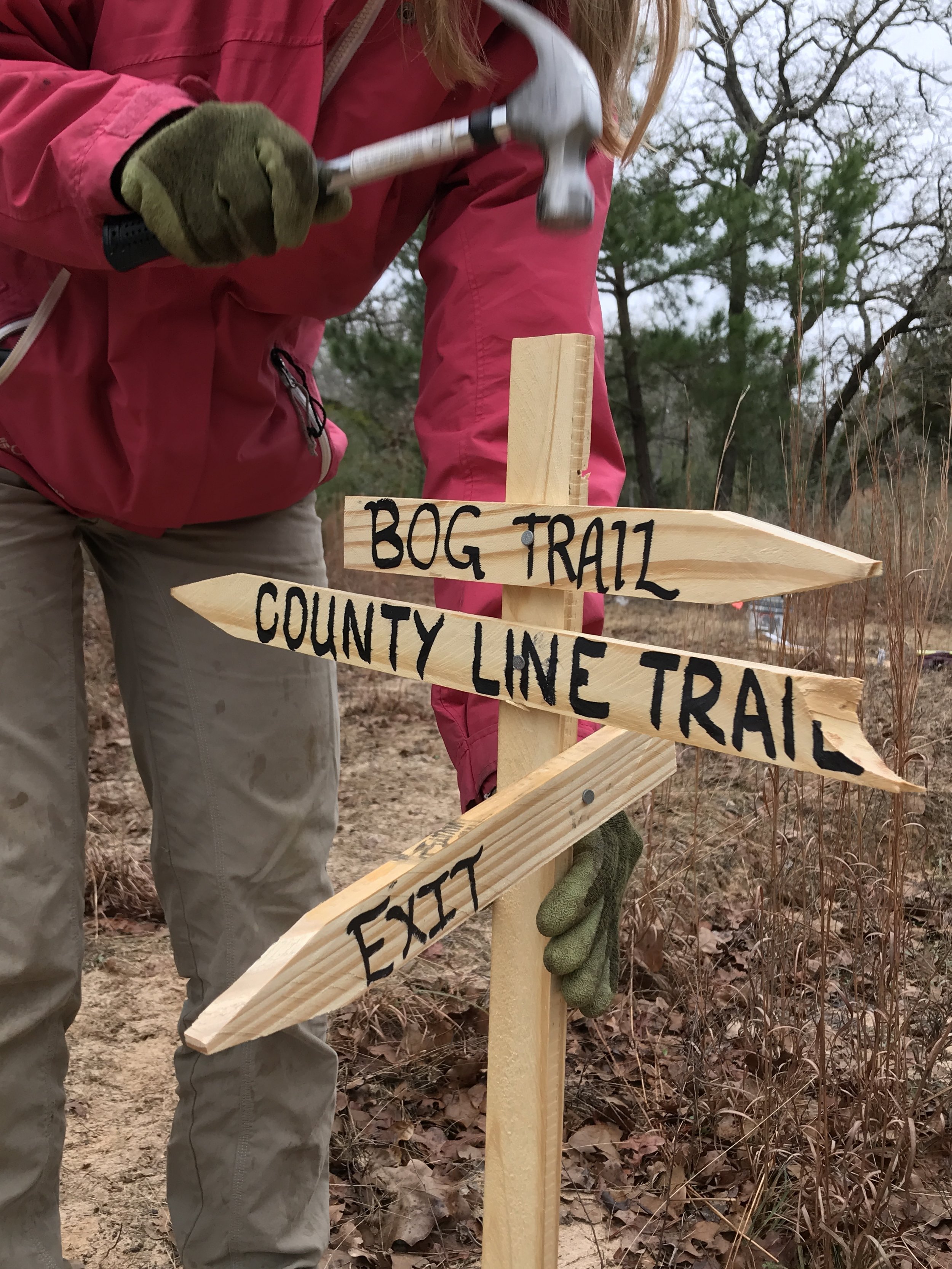

On Saturday February 9th, volunteers braved cold and rain to reach Yegua Knobbs Preserve but were pleasantly surprised when they arrived to find sunshine instead. Volunteers broke into two teams to tackle unmarked trails and a vanishing fence line.

The fence team undeniably earned their blisters, installing hundreds of feet of barbed wire fence along the boundary of YKP to keep roaming cattle from intruding on sensitive habitat. They pounded t-posts, strung wire, clipped, and tied their way across the eastern border of the preserve.

The smaller sign team installed trail markers at six trail intersections in the preserve and mastered the art of the straight hammer swing. They can’t wait for the next field day at YKP on May 11th for our signs to be put to the test by wandering hikers.

You can find information on more Second Saturday Service Days and the May Field Day at pplt.org/events. .

Yegua Knobbs—Where Life is Always Wild

By Larry Gfeller

Ansel Adams, a luminary conservationist, had a philosophy rooted in his deep belief that nature and beauty, particularly as symbolized by wildness, were essential elements of the human soul. It is this same belief, 31 years after his death, which guides the stewardship of 302 acres of upland woods near McDade, Texas, protected by Pines and Prairies Land Trust (PPLT). The property is known as the Yegua Knobbs Preserve (YKP).

The Yegua Creek forms in Lee County (named by the Spanish, Yegua means “mare” ) and is the primary tributary forming Somerville Lake. The knobbs refers to a small line of seven forested sandstone mesas 1 ½ miles south of Knobbs Spring in northwestern Lee and northeastern Bastrop Counties that run between the Colorado and Brazos river drainages. The preserve contains some of these mesas (this number remains contentious). It sports woods, hills, pastures, a spring-fed bog, rare plants, interesting geology and valuable habitat for the endangered Houston toad. Today it is a quiet place of serene beauty, but its history is right out of a B-grade Western movie.

Yegua Knobbs was a stronghold for a gang of outlaws known as the “notch-cutters,” who cut notches in their pistol grips after each killing. Why Yegua Knobbs? It was an immense thicket with plenty of hiding places close to the Williamson, Lee and Bastrop county boundaries—making it easy to evade jurisdictions. Confederate veterans had little to return to after the war and many were desperate. Joining an outlaw band was an easy way to support themselves. Cattle pens were built in the nearby town of McDade and buyers and sellers had a connecting railroad. After four years of war, the area was rich in unbranded cattle, but it was just a matter of time before the notch-cutters began stealing branded stock as well.

They perpetrated cattle rustling, gunfights, brazen murders, and general hell-raising, terrorizing McDade. In 1875, far removed from local county law enforcement, citizens took matters into their own hands and launched a series of vigilante actions that resulted in multiple murders and a string of seemingly unending retaliatory violence for nine long years. A turning point arrived in 1877 when the vigilantes interrupted a city wide dance, took four suspected outlaws out and lynched them. This slowed the mayhem for awhile, but in November 1883 two men were murdered in Fedor, and in a separate incident a second man was robbed, beaten and left for dead. The notch-cutters were back! The deputy sheriff investigating the matter was soon shot dead in McDade. Four suspects were promptly hung and three more outlaws were executed on Christmas Eve 1883. This led to a showdown gunfight in front of a McDade saloon on Christmas Day. The ensuing gun battle left three more men dead in the street and put an end to the notch-cutter saga. Still, unrelated violence and gunfights plagued McDade for nearly another thirty years. It was a rough town.

YKP as we know it today was also born of protracted conflict. This time the law determined the outcome. In the late 1990’s the Alcoa Aluminum Corporation proposed to expand strip-mining operations into Lee and Bastrop counties. In 1999 a grass-roots organization, known as Neighbors For Neighbors (NFN), formed in opposition to Alcoa’s strip-mining plans as well as to fight efforts by the city of San Antonio to import ground water from Alcoa’s property in those two counties. Eventually, NFN discovered evidence that Alcoa had been violating the Clean Air Act at its Rockdale coal plants. In the end, NFN successfully sued Alcoa over those violations, resulting in Alcoa paying several million dollars in fines. A tidy amount of those fines made their way to the Trust for Public Land and PPLT, with the stipulation it be used to protect land that was forested to support clean air as well as contain toad habitat. In 2004, PPLT purchased what is now YKP from private landowners who sought to preserve their land from intense development.

Together with U.S. Fish and Wildlife and the U.S. Forest Service, PPLT began a long process of wildlife habitat restoration on the property. Today, the property is managed as a wildlife preserve. PPLT board member and land steward Travis Brown says, “Our goal is to ensure this unique property remains wild and natural—that it provides the best possible habitat for wildlife.” The preserve has undergone a regimen of prescribed burns, large-scale mulching, brush removal and clearing of understory from the bog and springs. To date, several hundred feral hogs have been trapped and removed and public dove hunts have been conducted in concert with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department's Public Hunt Program. Deer hunting is not permitted in the preserve. As part of the wildlife management plan, a twice annual bird census is conducted on field days open to the public. Nest boxes dot the acreage.

YKP is not a public park, nor is it ever intended to be. It’s there to provide a protected home for a rich and varied population of wildlife. This is why it is opened to the public only at specified times of the year, to accommodate carefully-vetted special requests, or to conduct research. In 2015 Cristin Embree, board member and registered professional archaeologist, began offering cultural resource field days in recognition of the storied history of the land. The public is invited to help assess, research and protect archeological treasures in the preserve. This is a new and untried endeavor for PPLT, although there appears to be ample reason for optimism. Well before the notch-cutters, the area may have been used by a variety of historic and pre-historic cultures, especially as a potential stopping point for travelers on the celebrated El Camino Real trail. YKP is also believed to have been a location for an underground commercial kiln during the 1850’s—one of three possible area sites for the old Knobbs community. The Knobbs spring, a good source for water, is nearby, as is Marshy Creek. It is also home to a few species of rare plants, one of which (bladder wort) is carnivorous.

Walking the land is an experience Ansel Adams would have enjoyed! During early morning or late evening twilight, the place is teeming with animals, free to live their lives without encroachment. Because of the undisturbed nature of the property, it’s a veritable bird sanctuary. Near the wetlands and natural bog, silver and holding sunlight, cat tails and water lilies abound. If you’re quiet, beaver can be spotted swimming near their lodge or making improvements. You can spot Kingfisher, Osprey and Egret as the perch rise to an evening hatch, all rejoicing in their private Eden. This is ideal unspoiled habitat for the Houston toad. Deer gaze curiously from woodland edges as if they had never before seen a man. Native plants and trees grow free and unmolested by the avarice of development, a mixture of hardwoods and loblolly pines between islands of wispy waving bluestem, Indian grass and starred with wildflowers—the Post Oak Savannah of a hundred years ago! From atop the knobbs, you can see for miles, perfect for appreciating nature’s fecundity or—not so long ago—spotting unwanted lawmen and local vigilantes.

Created from a crucible of conflict at the crossroads of competing interests, preservation and protection is the obsession today. Despite conspicuous progress, threats remain. Even though the land is protected by PPLT in perpetuity, caring for it properly is a big job. Sympathetic volunteer groups, local residents and PPLT board members provide most of the brains and muscle behind conservation activity. “We need more and better land stewards and more volunteers,” Mr. Brown says. “One problem is the site’s remoteness. . .it’s pretty far out of the way for people to travel to regularly.” Given the shortage of wild open spaces left in Texas, balancing the demands of a growing population with land protection and conservation is problematic. A nearby coal strip mine continues to grow closer and closer to YKP, devouring massive amounts of groundwater as it impacts aesthetics and air pollution. Fights over water rights have been a part of life in Texas since the early days and the wars continue to rage today. Water rights for thousands of acres in Lee and Bastrop Counties have already been bought up, aimed at supplying San Antonio and Austin.

What, then, is the purpose of Yegua Knobbs Preserve today, you ask? Texas Highways recently reported:

“In a 1905 survey of Texas mammals, only the bison, elk and Caribbean monk seal had disappeared from the state by the end of the 19th century. During the 20th century, they were joined by the gray wolf, red wolf, grizzly bear, black-footed ferret, jaguar, margay, bighorn sheep and manatee in the list of species gone from Texas.”

The purpose of YKP is incredibly simple—to hold on to key habitat that supports the web of life.

Miracle by the River

By Larry Gfeller

Q: How is it possible for fifty eighth-graders to have more fun on a weekday than on the weekend?

A: By busting ‘em out of classes, loading ‘em up and heading ‘em out to the Lost Pines Nature Trails/Colorado River Refuge!

That’s exactly what happened in late April when officials from the Trinity Episcopal School in Austin asked Pines and Prairies Land Trust Executive Director Melanie Pavlas to sponsor an educational field trip ‘down by the river.’ Melanie immediately reached out to the local Texas Master Naturalist chapter and sealed the deal. The naturalists jumped on the idea and agreed to host the event.

Then, on the appointed day, two yellow school busses, teeming with barely official teenagers, were met by an escort at Bassano’s Italian Restaurant parking lot, and carefully guided into the wilderness by way of quiet, obscure neighborhood roadways. Retired golfers along the route stared like cattle, no doubt convinced the busses were lost.

For their part, the naturalists were excited to show off recent county improvements to the LPNT but were also stoked at the thought of helping young people discover the treasures of pristine riparian habitat. “And to your left, ladies and gentlemen,” bellowed the M.C., “let me introduce you to our main attraction of the morning, the Colorado River. It originates northwest of here in Dawson County and ambles 600 miles through numerous cities, including Bastrop, on its way to the Gulf of Mexico. It’s the only river in Texas to originate and terminate all within the borders of our state.” All eyes turned upon the mighty river, like kittens tracking a light on the wall. After the obligatory warnings about fire ants, chiggers, poison ivy and poisonous snakes, the only audible noise was the gentle rhythm of the river. . .they stared as silent as owls.

For those of us for whom age 13 is but a distant and foggy memory, recall that it’s a time of awakening hormones, ersatz social circles and ill-fitting training bras. To keep this group focused and engaged for two hours—we thought—would require something on the order of a three-ring circus. The group was split, then, into three groups: Green, Red and Yellow (go, stop and caution?). We would be rotating among three learning stations, which required near military precision from a cohort known for the attention span of ferrets. We were stunned. It was an active group for sure, but they demonstrated a thirst for the outdoors no one expected.

Station #1: River Wildlife. On the table in front were arrayed animal skulls, pelts, bird nests and snake photos. As the instructor began asking rhetorical questions, the youngsters bubbled with curiosity, clearly enchanted by the wild things that called this place home. Food, water, shelter and space—the four requirements for survival were served up, along with ample personal experiences everyone shared throughout the session. They didn’t need an instructor, they needed a moderator.

Station #2: Wetlands Ecology. Connections were drawn among plants, animals, weather, terrain and hydrology—a self-contained neighborhood of interdependency—every bit as complex as a modern city. Heads nodded in understanding, hands shot upward overflowing with questions and answers, stimulated by a bowl of candy to reward participation. The impacts of habitat fragmentation, draughts, floods and pollution were juxtaposed against a desperate need for protection and conservation. Rich mental protein for young minds.

Station#3: Nature Hike. Each group was further sub-divided; one of which went east along the river, the other west. The students were like avatars in a make believe world, stopping to examine a small snake, glimpsing a wading white egret, marveling at the ageless towering cottonwoods, contemplating the geology of eons. At one point, we just stopped and listened to the chattering of the forest, brimming with life—an adolescent game of connect-the-dots. The forest and river were exquisitely beautiful. Some narrative was inevitable, but we didn’t have to worry too much about content; good experiences ultimately speak for themselves.

After everyone rotated through all three stations, we gathered for one last group pow-wow for summation and final arguments. The busses rolled into the parking lot. Two hours, exactly! Expecting borderline chaos, we instead received the gift of appreciative enthusiasm. The moral of the story: never underestimate the power of nature! As we left them to their lunch and a short swim in the river, thoughts were going around in my mind like clothes in a dryer. When you know the magician’s trick, the only wonder is in its obviousness: among this group of bright young people no doubt will one day spring doctors and lawyers, scientists and mathematicians, mothers and fathers. Can there be any more compelling mandate to protect and conserve outdoor spaces than to provide a lifeline to our starved urban culture? It may be the most effective way to illustrate the hardest lesson in life: when things are gone, they’re gone. They ain’t coming back!

Going Native at Billig Ranch

by Larry Gfeller

This is a follow-on to“Choosing a Path of Stewardship.”

It was late afternoon and the sun was angling down. Thunderheads boiled overhead. The next morning the sky was milky blue; the ground damp from the evening rains. The land smelled of the dampness held in the earth. Work opportunities were dragged out in April, but, in the end, native grass seeds made their way into the ground at Billig Ranch. After a period of some uncertainty, it appears our eradication of mesquite trees in February was successful. Still more assaults were done in May and June—we will schedule as many sessions as it takes.

Land steward David Vogel was anxious to get the planting done because timing is everything.

Little did he expect persistent rains to present the problem they did. In addition to struggling with the weather, we appear to have a new problem—feral hogs! While we study methods of control, David points out the issue may not be all bad, “Historically herds of bison periodically churned up the soil, so native grasses are adapted to some degree to such soil disturbance.” Still, unless the hogs move on to greener pastures, wildlife biologists statewide know the damage they can inflict. It’s a new challenge. . .an additional opportunity to learn.

The science of planting native grasses can be complex.

The terrain at Billig Ranch, like much ranch land throughout Texas, was overgrazed. Without adequate topsoil, moisture absorbability becomes a problem real quick. We used a method known as no-till cultivation. No-till agriculture is nothing new, although this form of planting has gained renewed popularity in the agri-business industry of late. Actually, it’s been around since man first scratched the earth and dropped in seeds. The ancient Egyptians, the Sumerians and the Incas of South America all planted their crops by poking the ground with a sharp stick, dropping in seeds, and then tamping the ground with their feet. Instead of sharp sticks, we opted to rely on a specialist. We used the equipment and expertise of the Wildlife Habitat Federation (WHF), under the direction of Mr. Jim Willis.

Because of the unusually heavy rains this spring, our job took longer.

After the first two days of planting the rains came, interrupting our plans. Waiting for the rain to stop is an unaccustomed delay in Texas; however, the clouds finally cleared and we were once again able to work in the field. A total of four days were invested in fully covering our targeted acreage. We planted a mix of Big Bluestem, two varieties of Little Bluestem, Sideoats Gramma, Green Sprangletop, Indiangrass and two varieties of Switchgrass. With funding help from the National Resource Conservation Service (EQUIP program) and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (LIP program), Jim Willis’ crew set the stage for a sustainable natural ecosystem to emerge. Fortunately, the rains continued, providing near ideal conditions to get this conversion process launched properly.

After waiting for rain to cease long enough to plant, many of the ridges on the property became as hard as a crowbar, literally overnight, and no-till coulters were needed to cut into the soil. This occurred even when other lower lying areas remained wet. Another issue is that native grass seed is generally lighter and fluffier than other seeds. To solve these problems, the equipment used was a 12.5 ft. Truax no-till seed drill, an implement which has coulters in front to cut through stubble and litter, double disk openers to open a trench in the soil for the seed to drop into, depth bands and hydraulic controls to regulate the planting depth, and press wheels to insure good seed-to-soil contact.

This ain’t your father’s seed drill! For instance, the floating double disk openers are staggered to keep trash from accumulating and restricting planting. Using such a drill helps to eliminate more of the human factors that might restrict getting a good stand of native grass. The idea is to plant at just the right depth without costly seed bed preparation. Not only does this save a lot of time and expense, it also provides for accurate seeding rates, precision seed placement and minimal disturbance. It happens with little loss of soil moisture and nurturing organic material.

Jim related the logistics of getting the equipment on site:

“We transported the drill with a ¾ ton truck and tandem wheel trailer that was rated at 10,000 GVW lbs. The drill weighs 8,400 lbs. and the trailer close to 2,000 lbs., so we were at maximum towing capacity. We also transported a 12,000 lb. 4WD John Deere tractor with a large diesel truck and flat-bed trailer (similar to an 18-wheeler). The total distance for transporting all equipment from Cat Spring to the Billig Ranch was 82 miles.” In other words, it was more of a chore to safely transport the equipment (it took a crew of three men) than it was to actually sow the seed (a one man job).

The science of no-till planting is intriguing. According to the Pennsylvania Nutrient Management Program, no-till planting leaves more than 30% plant residue in its aftermath. This is important because more plant residue encourages rain to infiltrate the soil and reduce evaporation. No-till also has been shown to leave higher populations of beneficial insects and a higher microbe count. These microscopic critters in the ground can make the difference between a lush inflorescence and a half-naked, starved plot. From a practical standpoint, there is less dust and debris created compared to conventional tillage—and less fuel used to get the total job done. “Although other planters might be easier to transport, easier to use and faster, these advantages are inconsequential when considering the results,” Jim Willis says.

Here’s another factor to consider: native grass seed is more expensive to purchase.

There are good reasons for this. First WHF harvests some of the seed from the same ecosystem it is to be planted in because it needs to grow and compete with endemic invasive species. Each season WHF sends locally harvested seed to Bamert Seed Company where it is cleaned, analyzed and bagged. These seeds are then mixed with germplasm, other seeds selected at USDA/NCRS Plant Material Centers which have been grown by commercial seed growers like Bamert. Most of the grass seeds planted in the mix at Billig were commercial varieties from early successional plants (those that germinate the first growing season), medium and late successional varieties. Willis says, “Some of the late successional seeds (including the local ecotypes) may take five years to germinate—which is nature’s way of dealing with factors like droughts or floods.”

Despite the higher cost, consumers need to focus on value per unit of cost.

Buyers should insist that native grass seed have a seed tag showing it was tested just before being shipped and buy it on the basis of PLS (pure live seed) pounds. This is a calculation which insures the highest purity is matched with the highest germination rate and is expressed as a percentage. PLS pounds may only be 40% of clean seed bulk pounds, therefore halving the quantity of quality seed needed, according to Mr. Willis. He goes on to state, “WHF always tells its customers to buy from reputable seed companies that sell on a PLS basis.”

While this is PPLT’s first major attempt at conversion to native prairie grasses, WHF has been at it since 2004. The original motivation for WHF was (and still is) restoration of habitat for upland game birds. After receipt of a federal grant to do just that, WHF established the first quail corridor in the state. Texas A&M University researchers discovered 31 species on the original 200 acre test plot after 5 years of proper follow-up management. In the beginning, the quail corridor resulted in WHF collaboration with landowners controlling 2,000 acres over two counties. Today the organization is working with landowners who control 40,000 acres in a dozen counties. Jim says, “No one wants you to be successful more than we do. We like to work with people who also have a passion for restoring prairies.”

But this is not a “slam dunk.”

Ample rains received at Billig this season are a questionable blessing. Invasive species will be difficult to control if not sprayed precisely when these plants are growing most actively. Some invasives (which have lain dormant for years) may germinate after competition is reduced by the first herbicide treatment and then jump-started by recent rains. Early successional natives may not be able to compete with the early successional invasive species. If that happens, the game plan changes: selective herbicides, controlled grazing and prescribed burns would need to be used at just the right times to give natives the needed edge over invasives. Because some natives take five or more years to germinate, this becomes an endurance contest, or outright war. Several battles may be required to win the war!

As for PPLT, there are several goals in mind here.

As our first major restoration effort, the Billig experience will serve as an experimental clinic for our other rehabilitation projects. Another major goal is to create a healthy savannah to support a diversity of insects, birds, herps and mammals—to include enhancing survivability of the endangered Houston toad. We intend to monitor the impact on local wildlife populations. Finally, we envision a meaningful educational tool for both organizations and individuals interested in studying our model for environmental sustainability. Stay tuned for occasional updates about our journey. . .we mean to do Mr. Billig proud!

ERWIN BILLIG: CHOOSING A PATH OF STEWARDSHIP

By Larry Gfeller

It’s comforting to stand among a sprawling matrix of wildlands—without people. Nothing much but weather and distance, punctuated every so often with ranch gates, and to the south the endless murmur and occasional sun-flash of semi’s on Highway 21. There’s something basic and elemental here. The day is measured by sun and shadows; nobody cares what time it is. There’s a sense of fit and symmetry, balance and rightness: the fertile soil, the free-range swatches of savannah peppered with trees, bathed in sunshine and teased by the breeze at my back. Life is all around me—and standing out here, now. . .I take the time to notice. It’s as if I’ve stumbled upon a secret society of plants and animals—a snakeless Eden—living and supporting each other, undisturbed by the hustle and noise of human activity. Today I have exclusive rights to observe and appreciate. I am accepted immediately, integrated into the scene without fanfare. Perhaps John Muir best described the process: “Presently you lose consciousness of your own separate existence; you blend with the landscape, and become part and parcel of nature.” As I soak in the distant boundaries of Billig Ranch, I’m warmed by the thought that all this natural beauty will be preserved for posterity.

When Erwin Billig gifted his 677 acres in 2006, he commissioned Pines and Prairies Land Trust (PPLT) to maintain it as a nature preserve. Today it’s a quiet refuge, open to the public only rarely. There is currently a cattle lease and a small human footprint on the acreage (a rental home, outbuildings, a barn), but it’s small and insignificant compared to the larger purpose Mr. Billig envisioned. Cattle leisurely graze the land, among them a small herd of longhorns. But as I look around, red tails surf the thermals overhead, you can glimpse flocks of waterfowl, song and game birds. Butterflies nectar among the wildflowers and grasses. Several glistening ponds dot the landscape, providing critical breeding opportunities for the endangered Houston Toad. Wildlife abounds. Mr. Billig knew this land would only grow more rich and diverse with the passage of time. The man loved wild country and it was a bond. Peace of mind and satisfaction are two significant byproducts of the protection offered through conservation easements.

Desired outcomes seldom occur by accident. PPLT designates land stewards for its properties; Billig Ranch is watched over by David Vogel. In line with Mr. Billig’s vision, David is looking to take the land back to an earlier time when agriculture was not the primary use. He intends to take the property native. This is a long-term goal that will take years to realize. The expectation is to provide habitat for even more wildlife diversity. David says, “With the recent endangered listing of the Monarch butterfly, opportunities exist to make Billig a Monarch sanctuary.” Billig Ranch is visualized as a demonstration site for native prairie restoration and wildlife management practices. The plan is to open it up for various educational efforts as well.

When considering a switch from imported agricultural forage grasses, conversion to native grass prairie land is neither easy nor inexpensive. Partners are required . . . and PPLT has engaged some significant ones. For the conversion effort, the National Resource Conservation Service has extended a helping hand through the Environmental Quality Incentive Program and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department has signed on through their Landowner Incentive Program. The Wildlife Habitat Federation is an active consultant on seed selection and site preparation and talks are ongoing with the Native Prairies Association of Texas, who have expressed interest in also becoming a partner. As to the longer-term future of Billig, PPLT has met with a biologist from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, working together on plans to identify other restoration projects at Billig Ranch of mutual interest.

For 2015, there are two projects scheduled which will target planting about 100 acres in native grasses. The Wildlife Habitat Federation will do the actual planting, using their tractor and a Truax No-till seed drill, but there’s preliminary work to be done to get the site ready for planting. In February, a group of volunteers under David’s supervision worked on the first scheduled planting site, treating honey mesquite with herbicide. This was a basal treatment with Remedy and diesel, mixed with a small amount of blue dye. The lower portions of each trunk were sprayed thoroughly during one of the warmer cracks in winter weather. We will need to visit the site as spring unfolds to determine effectiveness. More work on removing competing vegetation is planned before we prepare the land for planting.

Planting native grasses is one small but important step in safeguarding the web of life. Billig Ranch, like most of our properties, is a work in progress. Texas was the largest state in a once vast ocean of tallgrass prairies that swept through the Great Plains from Mexico to Canada. Today about only one percent of this treasure remains, making it the most endangered piece of large ecosystem in North America. Reclaiming our heritage, one bit at a time, will not only draw the wildlife for whom Erwin Billig dedicated his land, but it will help preserve an environment whose legacy is anything but assured. One day in the not-too-distant future, we hope students, researchers, naturalists and people of all walks of life will be able to enjoy the adventure, discovery and benefits that come from taking an active role in ecological restoration.

We will keep you posted from time to time and hope to bring you interviews with some of the players and partners involved in planning, preparing and executing David’s prairie grass conversion project. Landowners and readers of this blog are invited to raise questions, make comments or share experiences. We’d love to hear from you!

ON A COLD DECEMBER MORNING

by Larry Gfeller

Albert Pecore did not get where he is today by fortuitous accident; he nurtures a 196 acre spread on choice Fayette County ranchland, rich in native pastures, water features and a prime example of nature’s munificence. Hidden away in this natural wonder is a farm house like no other. . .starched white, multi-leveled, immaculate and uniquely his own design. You see, Albert is a man of vision—a retired architect. Over the decades he and his wife Wilda have carefully planned and sculpted the property to be as free and natural as it once was over a century ago—before the plows and cash crops and over-grazed plunder that so often robs our land of its natural wealth. Central to those plans is a timeless conservation easement through Pines and Prairies Land Trust; on this chilly December day, it was time for the annual site monitoring visit.

David Vogel and Cristin Embree are the PPLT board members conducting this visit; we start by climbing two flights of outside steps to the upstairs living room. First David catches up on recent history. . .what has been accomplished since last year’s visit (as a member of the PPLT Land Committee, David has conducted each monitoring visit from the beginning). Then Cristin, a professional archeologist, inquires about the old foundation she noticed not far from the house (remnants of the Emil Schlabach homestead), pointing out that it appeared on her map as an historic feature. She notes it can be protected by a preservation easement, if the Pecores decide to add it, and she urges them to consider it. Preservation easements are conservation easements that protect properties that have historic, architectural, or archeological significance. Preserving the past helps define the present, a truism Albert already appreciates.

Before departing to examine the property, Wilda provides a tour of their unusual home, stopping first to tenderly set a vinyl record on an antique record player—warm, joyful Christmas music fills the house. The home stands two stories tall with living areas interconnected by windowed hallways and internal stairs on the south end; from the side view, it evokes the letter “H.” A majority of the living space, be it elevated or ground floor, opens to spacious verandas overlooking the property to the east and west. On the upper east-facing portico stands a spotting scope on a tripod—Albert is intrigued by hawks. The home is clearly a labor of love that can only be described as singular and refined. He designed and partially built it himself.

We are accompanied by the family dog, Macy, a bouncy, playful spirit of energy.

On the ground level, there is a completely self-contained apartment—perfect for visiting guests and family. Across a stone patio on the east side lies another separate living space, complete with washer/dryer, bathroom, kitchen and generous windows. Macy is not allowed in this room; it is permanent refuge for Charlie and Shelby Texas (two lounging felines)—the family cats. It will not be Macy’s only disappointment of the day.

We gather by the barn and prepare to tour the property. Everyone piles into Albert’s 4-wheel drive Kawasaki, making it look like one of those third-world busses—packed in and over peopled. This is when Macy insists she also can fit, only to be disillusioned. She is so eager to go she has to be removed several times. At the final call, she is restrained on a stationary leash. . .as we pull away, she emotes a sorrowful look, as if considering her own bill of divorce.

Albert is an engaged and fervent guide, “I stopped making hay on this property fifteen years ago.” With a steady hand, he steers us around obstacles and through the savannah. As we negotiate the sprawling acreage, the conservation value of the land becomes apparent. . .an immense man-made pond, a section of riparian habitat and 38 acres of coppery native little bluestem singing in the December wind, part of which was recently restored. There are traditional intruders, like king ranch bluestem, johnsongrass and yaupon, but the native grasses dominate, summoning visions of sweeping blackland prairie, natural and undisturbed.

In the distance, you can almost see the buffalo graze.

Albert has invested significant effort in learning his grasses, pointing out indiangrass, little bluestem, switchgrass, plains bristlegrass, prairie wildrye and eastern gammagrass as we roll along. He’s particularly fond of new discoveries of big bluestem, stopping to cut samples for closer study. He has even begun his own native grass nursery, transplanting specimens he has picked up along roadsides, ditches and easements. Albert has put down chicken wire to protect the tender roots from encroaching armadillos. The nursery appears to be thriving, even during the dormant season.

Ever the gracious hostess, Wilda is our official gatekeeper today. As we snake our way around, she opens and closes the substantial gates that protect each parcel of property (there are sixteen separate permanent pastures). As we methodically run each fence line, Albert points out his efforts to plant native grasses where they don’t occur in sufficient abundance. “With the help and expertise of the Wildlife Habitat Federation a blend of native grass seeds were drilled into pastures in need of rejuvenation,” he exclaimed. The work is year round: if not planting or transplanting grasses or maintaining a pristine fence line, he keeps a regimen of planting cool season rye and legumes in pastures that have not been converted to native grass. Albert and Wilda do this work without outside assistance.

Aside from his delight in native grasses, Albert is busy with other aspects of good stewardship. As we lurch and roll along, he points out brush piles and cut cedar—one job he does contract out—keeping some to benefit wildlife, burning others. He has introduced native pecan trees, closely monitors rainfall amounts, watches changes in the water table, manages erosion, and runs a small herd of cattle. Having tried just about every method once, Albert believes in “pulse grazing.” Instead of dispersing his small herd broadly over the property, he intensely grazes different sections, moving the animals frequently—just like the buffalo did.

During a private moment, while getting a closer look at his riparian area, I ask Albert why he is doing all this.

“After purchasing the property in the 1950s, I never did intend to farm. I started with cattle and a riparianeasement. I bet most of the farmers in Fayette County have never put pencil to paper regarding riparian easements. The federal government pays me $50 per acre per year. That nets out to probably be better than many farmers do running small herds or growing small cash crops,” he explains. Albert has three sons. He discussed entering his property into an over- arching perpetual conservation easement with all of them beforehand. They heartily agreed—preserving and protecting the land was important to them too.

“How has it been, working with Pines and Prairies Land Trust,” I asked him.

“It’s been a good experience,” he replied. “I signed up with PPLT in 2007. . .we’ve been learning together ever since.”

So David made his notes, complemented the Percores on their efforts and thanked them for their hospitality. Macy had already forgotten her earlier disappointments. Shortly, we were loaded up and ready to go.

In three hours we had witnessed what happens when man and nature cooperate. It used to be a mutual necessity, when the land provided life itself. Now, in this age of smart phones, Internet and international marketing agreements, technology has set us free and blurred our primordial connection with the land. The majority of Texas is privately owned. Although our relationship with the land may have changed, the truth has not. We still need each other. Only through enlightened landowners—like the Pecores—can we restore this vital connection.